As a teenage fuck up who had recently (and barely) graduated high school, I, of limited opportunities, joined the U.S. Army in the summer of 1983. I had never been outside the northeast U.S., and after advanced training, was first assigned to Fort Lee, New Jersey. Cool, I thought, I'd be close to my girlfriend, in Harrisburg, Pa.. But then, in what I would later understand to be in true U.S. Army fashion, a last minute phone call came in: I would instead be dispatched to South Korea, a country that seemed for my lovelorn heart to be on the other side of the planet.

Ostensibly, the U.S. was in Korea to deter (the Communist) North Korea from invading South Korea, though as someone I met there pointed out the presence could also have been to protect the two countries from re-merging, which had only been torn into half a few decades prior. For many Koreans, I would later learn, Korea was a single country, the 38th Parallel between utterly arbitrary, rendered asunder only by external politics.

In any case, if North Korea were to invade the south, we were the ones to spring into action, potentially giving up our lives for our country. It didn't come to that. Mostly it was a lot of hurry-up-and-wait.

The camp I was assigned to, Camp Stanley, had a library, a place of worship, and offered GI's weekend day tours to points of historical interest. But, like most of the enlisted there, my interests soon turned to the village (or "'ville" as it was called) right outside the camp itself. Probably every Army base around the world has one of these small towns attached to them, with easy pleasures for the enlisted: booze, greasy food, prostitution, and, if you knew the right people, pretty much anything else.

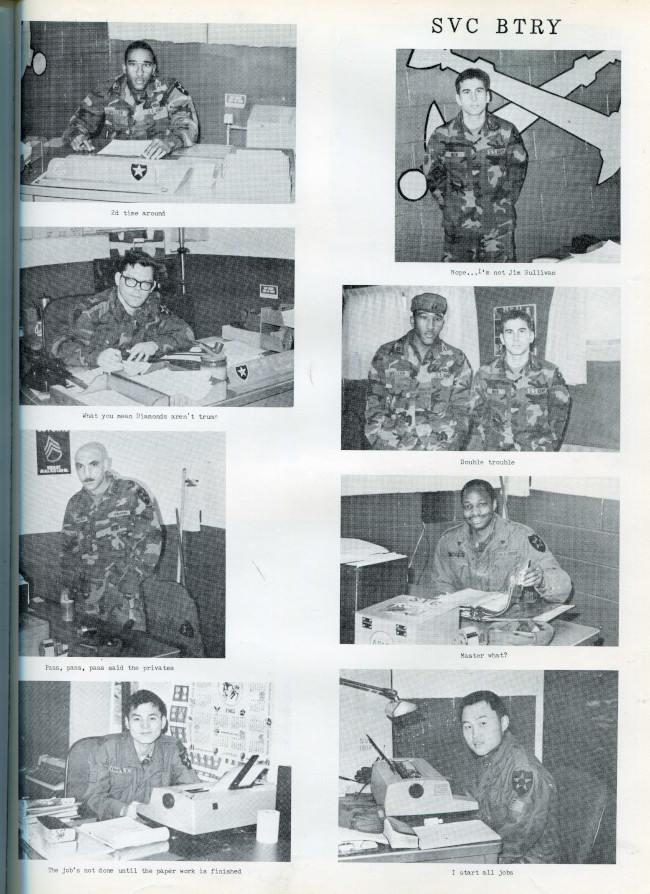

Specifically, I was dispatched to 2nd Infantry Division, 8th Field Artillery Battalion, Service Battery.

.

![]()

The unit was located at Camp Stanley Korea, a smallish outpost in the mountains near Uijeongbu, which was about halfway between Seoul and the DMZ border with North Korea.

![]()

I will say this about the U.S. Army. It does teach you to get shit done. You can stay up until 3 AM the night before, aided by drink and who knows what other enhancements, but come 5 a.m. you will have to rise from your bunk, move a truckload of spare parts onto an actual truck...

![]()

...then ride miles across bumpy dirt mountain roads in the back of said truck...

![]()

only to stop hours later to set up camp somewhere...

![]()

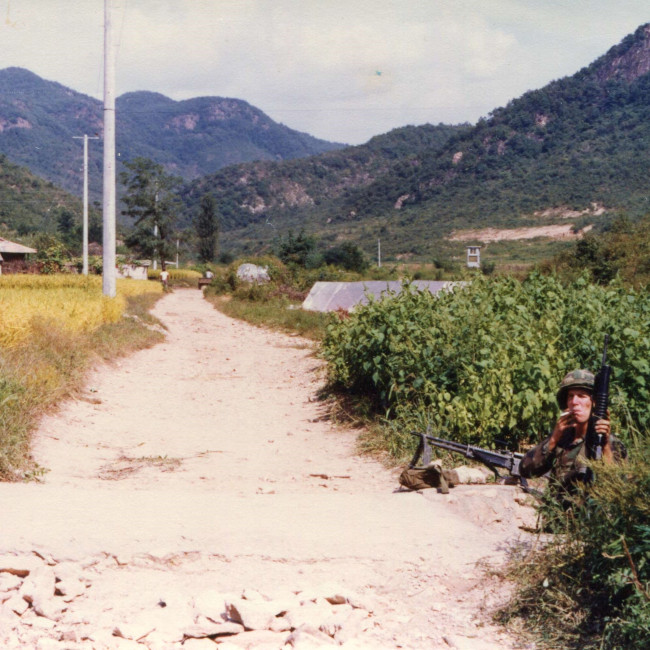

...and then pull guard duty.

![]()

There is no option of not doing this work. You couldn't "call in sick," or "quit." Especially not in another country.

![]()

But, if you're lucky, you'll retain at least a bit of this muscle memory of getting-shit-done, which can be vastly useful later on in life.

![]()

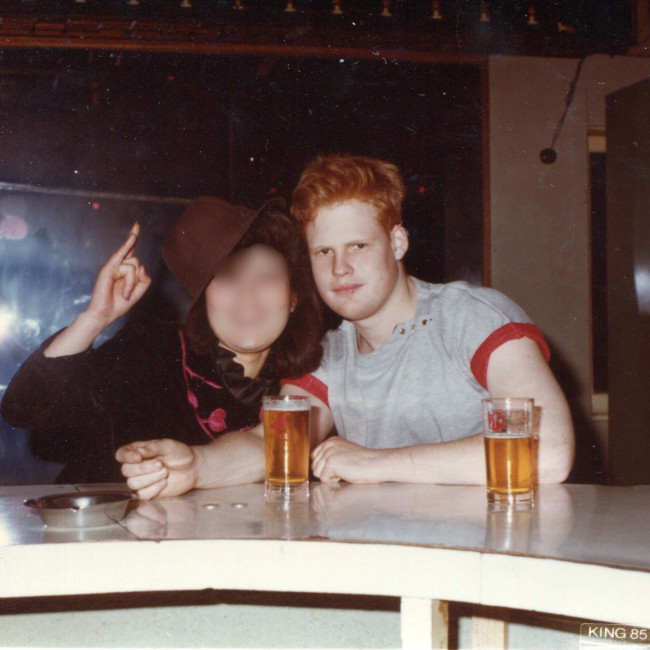

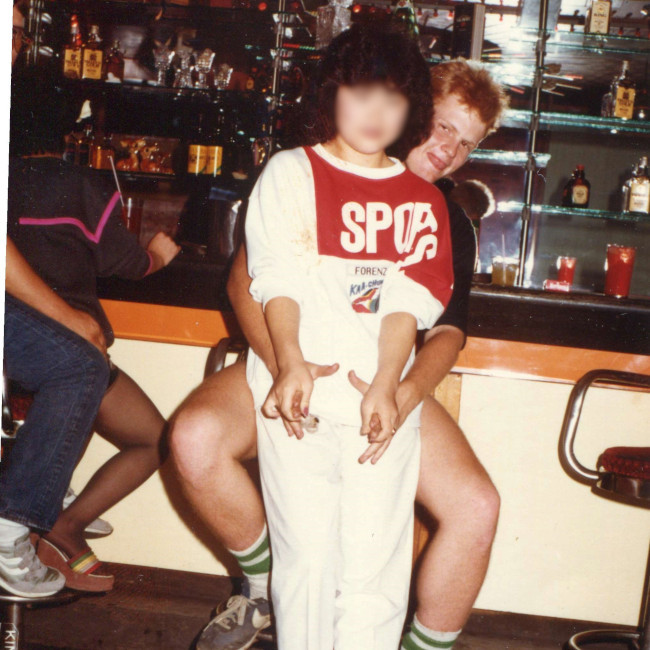

This was my friend and later roomie, John. It was John's second tour of Korea, so he had all the connects. He got a lot of shit for having me tag along, like some stupid little brother. The officers in charge of the unit thought he was corrupting me, the fresh new turtle, when in fact I probably pushing him over the falls in his own barrel. More on that below.

![]()

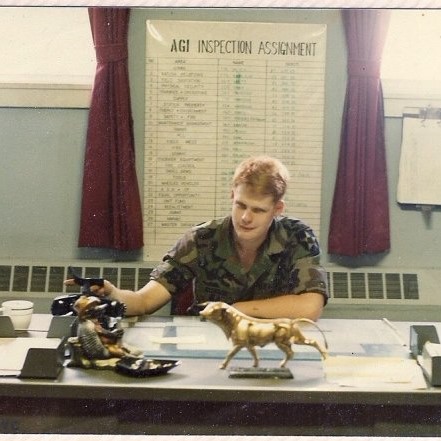

Where I worked, in the motor pool, maintaining a shelves of replacement parts for these trucks, as per my MOS. I was trained as a parts clerk (MOS 76C: "Equipment records and parts specialist") (& more on that skill below).

![]()

Most of these trucks were for carrying to the front line the actual artillery, 2 1/2-ton trucks, widely nicknamed "Deuce-and-a-Half." or just "dusinhaf."

![]()

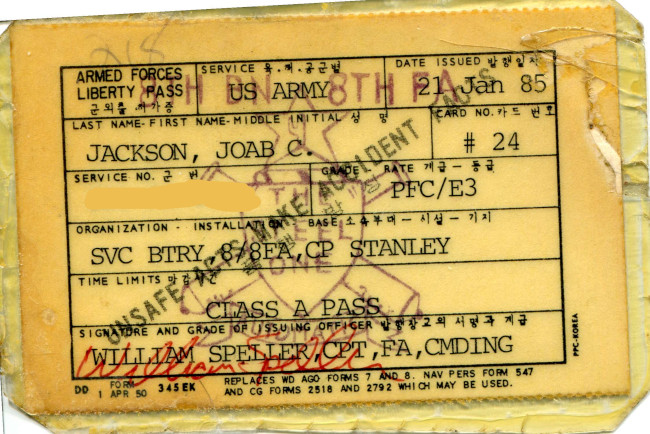

To get off base (and get back in), you needed one of these passes. Even then, you had to be back at night (Unless you got a coveted "overnight" pass).

![]()

Black marketing was a key to an enjoyable Saturday night! You could buy a fifth of Bourbon for $5 from the on-base liquor store, then trot downtown, flashing your pass at the gate, and selling the bottle in the village for $14...

![]()

...You then take that $14 back up into the commissary, buy a few more items that were, due to quirks international trade laws, in short supply within Korea, items like maraschino cherries(!), mayonnaise (!!). You could double your money buying a bag of these items, trotting them down to the 'ville (telling the guard they're "for your girlfriend") and selling to one of the "Mamasans" running a bar.

![]()

Take a few more trips to the commissary to double your money a few more times and you could soon have enough for a night out on the village. You could blow over $100 and not feel too bad because it was all just $5 to begin with...

So black marketing was a win-win for everyone except the international trade laws I guess.

![]()

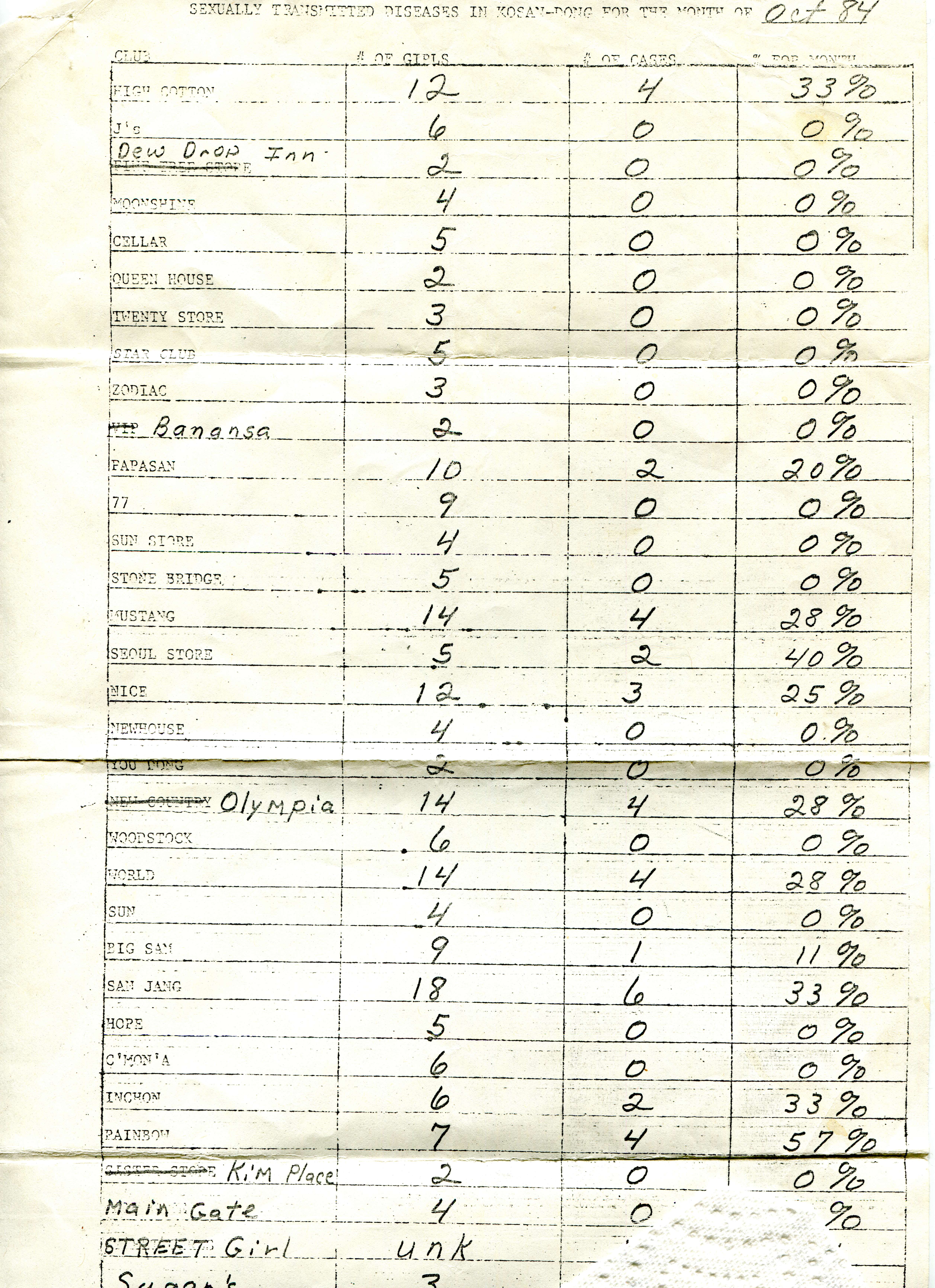

Speaking of monetary transactions, the U.S. Army didn't condone prostitution, but it didn't exactly turn a blind eye either. In fact, there was a box of condoms by the gateway into the 'ville, like one of those boxes of sand on the side of the road to help autos in slippery conditions.

When new soldiers arrived at the camp, they were given a class on the dangers of the bars in the 'ville. I can't remember much detail that the instructor, a barky drill sergeant type, got into: That the young women could have been sold into servitude to the mamasan by her parents, a bill that she would then have to work off in the bar, through drinks from lonesome soldiers, hook-ups that were $10, $20 for the entire night, or even by being some soldier's "girlfriend" for an entire month, $300.

"Here's my girlfriend, I bought her," we'd joke, tho in all fairness, I saw at least a few of these relationships grow into what appeared to be true love.

The sergeant did instruct us in one particular point however: That none of us in the room, no how matter cute or ripped, would ever be getting any "free poji" in the 'ville.

The sheet above would be distributed around the barracks by the Camp Stanley medical unit (with no identifying U.S. Army insignia, natch). It estimates the number of women working as prostitutes in each bar, and an estimated percentage of them who had a venereal disease (as reported through the GIs coming into the medical center to get treatment for their enflamed peckers). Why they didn't treat the women is anyone's guess. Politics, probably.

At this time, we hadn't heard of AIDS yet, but there were rumors of something called "Back Syphilis," that if you got it, there was no cure, and you wouldn't be allowed back in the U.S. It turns out that it was "pseudo-legendary STD," rumors of which had been passed along at least from the Korean war.

![]()

I only remember the word "poji" because the ladies I did get to know in the bars would laugh as they ran their hands through the short, soft, blond finely-clipped hair on my head, calling it "poji hair."

![]()

We probably weren't the most creative types, really there wasn't a lot to do with your downtime buried halfway up the mountains of South Korea with limited access to the outside world.

![]()

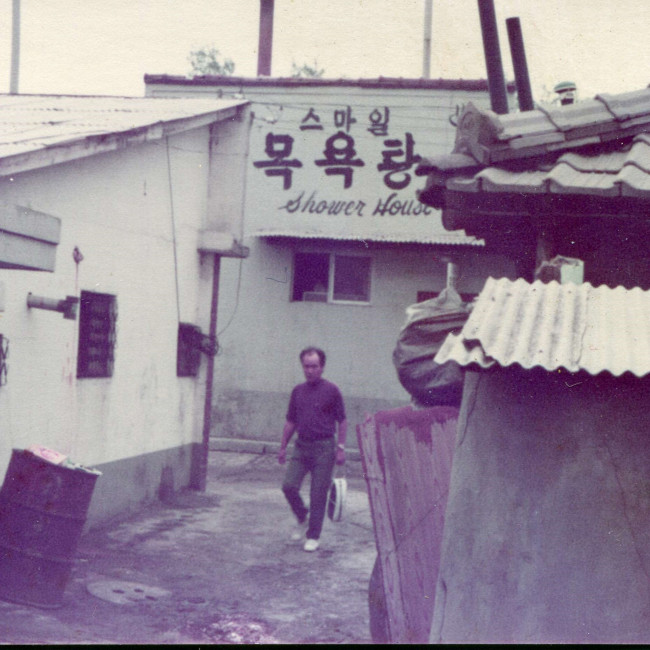

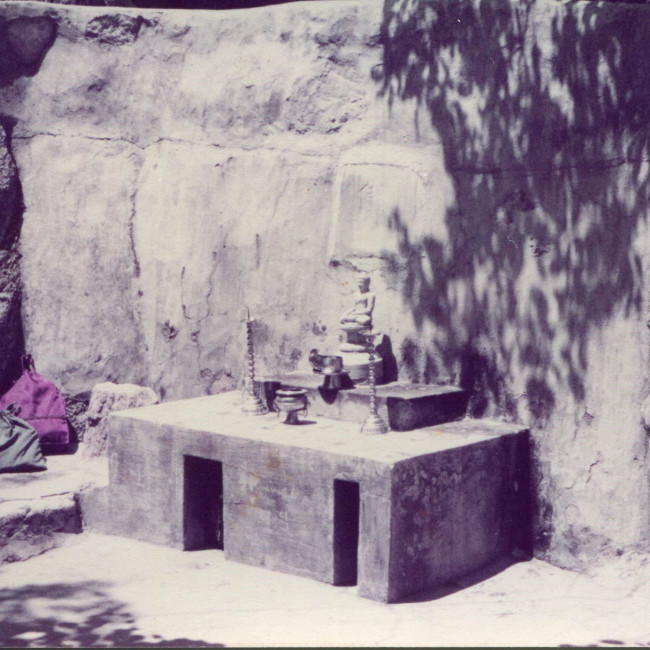

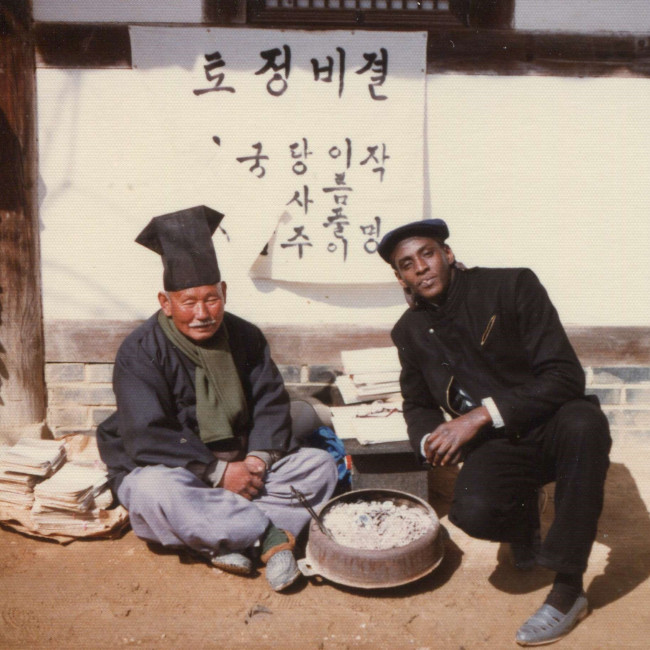

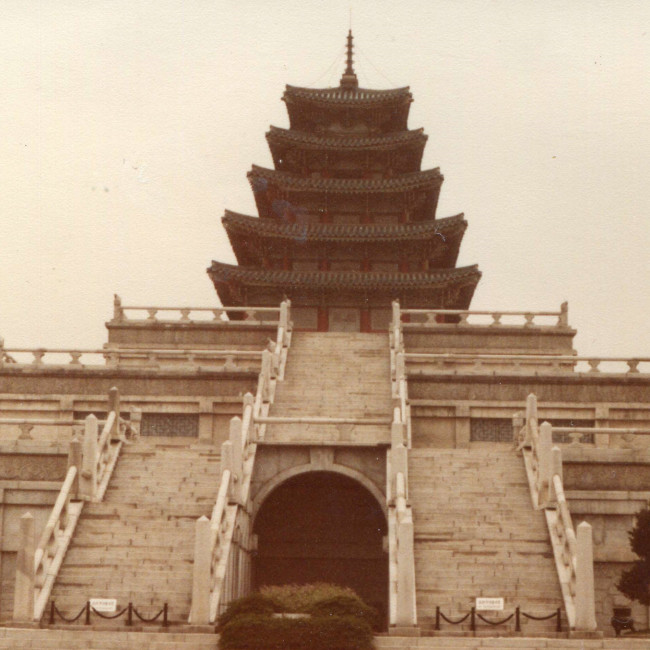

Of course, we could go explore the country on weekends...

![]()

Getting to know the local culture...

![]()

...Though sometimes with mixed results.

![]()

![]()

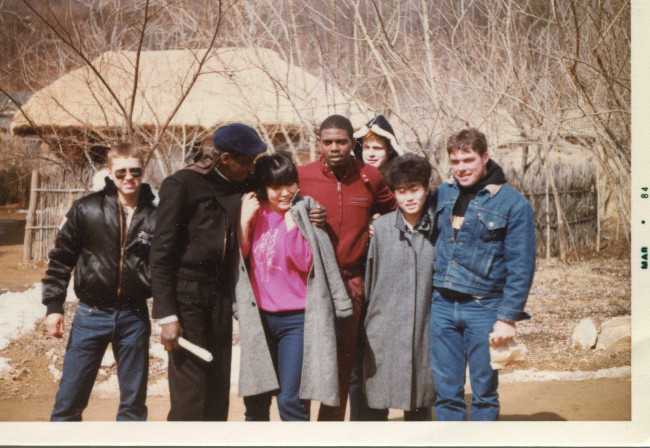

The funny thing about the Army enlisted is that we all were misfits, fuck-ups of one sort or another. Nobody with anything at all going on in their life would voluntarily choose to leave their home to serve. And yet, we all bonded as brothers in an uneasy family.

![]()

We also got to know our counterparts, the soldiers from the Korean ROK Army, for whom service was mandatory.

![]()

My roomate Jeff (left) couldn't leave the country when his wife was due with their son. He found out by telephone when the baby was delivered, an incredibly bittersweet moment.

![]()

A lot of nightly drinking occurred in the barracks.

![]()

And so there was a lot of stupid drunk behavior. I got that scar above my eye by being clocked for being a smart-ass (Not from her -- but from another GI I had told to fuck off).

![]()

For me, listening to music killed a lot of time (as always). A lot of premier Japanese electronics could be obtained cheap from the on-base PX. And, in the 'ville, there was a music store that only sold bootleg cassettes of the hit albums of the day, the track listings typed out on white cassette cover sleeves by hand. $2 each.

![]()

So, as I had mentioned, this was John's second tour of duty. He had already learned how to get the hook up on codeine, which we took to consuming on the weekends for kicks. To be clear, the stuff he could get wasn't the nasty 'tussin the kids in the U.S. sicken themselves with these days.

![]()

This Korean codeine could only be obtained by prescription. It was smooth stuff. A family could get maybe one a month. But John knew someone in Dongducheon who could sell it out back the pharmacy by the case. (Don't remember for how much, it wasn't super expensive).

![]()

Basically, the idea was to down about six bottles of this codeine in a row and utterly space out for the evening. Like forget-a-sentence-halfway-through-mumbling-it sorta spacey.

I would like to say that it was the anxiety of the unknown that led us to swill all that codeine, that we wanted to numb ourselves from the dark prospect of being fed into the war machine at any moment. But actually, I rarely thought about that. For me anyway, it was just my usual, ongoing appetite for chaos.

Dongducheon was right up on the DMZ, by the way, though this photo faces southwest.

![]()

On the top of the cap of these bottles was the slogan "Better Life Through Medicine." So we got shirts made with the "Better Life Through Medicine" logos on them.

![]()

Sentences were difficult enough to complete on the stuff, and conversations were pretty much impossible. Instead, we visited the local clubs in the 'ville, which had any kind of genre of music a young man could ever want. I preferred hard rock.

Here I am, wearing my "Better Life..." shirt, passively listening to Robin Trower or Neil Young probably, at a very high volume from the giant-ass speaker right next to me.

![]()

One Saturday afternoon, frustrated when the base went on full lockdown due to some DMZ-related hostilities, we tracked down the commander's assistant, who could forge commander's signature on the dispatch form (provided by yours truly) that would allow us to drive a Deuce-and-a-Half off base, and directly towards the DMZ hot-zone, to Dongducheon, just so we could pick up our codeine for the evening.

Today, I can't even fathom how many laws we broke -- both Korean AND the Army's. We basically stole a truck and uncaringly drove it into a tinderbox of internal hostilities, just to score that sweet, sweet codeine. Kinda amazing we didn't accidentally kick off another war.

![]()

![]()

We got back safely, though word eventually got around about our trip. It became something of a camp legend. I think it even reached our commander Captain Speller after a few months, though he never said anything. Tired of stunts like this, he might have already gotten John kicked out of the Army by that point.

![]()

Captain Speller was pretty much a level-headed and kind-hearted leader. But he had it out for John. And John had very little love for the Army.

![]()

Speller got John kicked out of the Army through a surprise room inspection that turned up considerable amount of weed in John's locker. Though not even bothering to hide the weed was really on John.

Nor did John help his case any by commenting as Speller and two military police (MPs) stood around John's locker, discussing how to handle the contraband. As John later explained to me, Speller volunteered to test the green substance in the bag to ensure it was marijuana -- he had gotten that training as an officer. The MPs said they had their own test. John then added, that he had already tested the stash, and it was, indeed, weed.

The woman in this picture,by the way, was not part of the Army. Rather, when we went out into field for extended multi-week exercises ("Team Spirit '84!"), she and a small caravan would follow along. She would trade nice warm bowls of ramen (with cheese, eggs or chicken) for the bland U.S. Army-issued pre-packaged Meals-Ready-to-Eat (MRE) we were issued for most meals. It was a no-brainer for us hungry soldiers and evidently the MREs fetched a good price on the black market (for hunters and survivalists I guess).

![]()

John was far from being the only one unhinged in that unit, however.

![]()

I was the machine gun operator for my squad. Not because of any skill I had -- M60s were pretty much spray and pray -- but because I was the largest, and could best hump the heavy weapon during hikes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Friends of mine who knew me before I went into the Army say it didn't change me much. I didn't come out particularly super-disciplined. But my successful service led University of Maryland to take a chance and grant me admission, even with my terrible high school grades. For the first two semesters I made the honor role, and graduated a swift three years after.