30 years ago I started my journalism/writing

career with HARRY, Baltimore’s original underground

counterculture newspaper.

Pre-Internet, HARRY was the only place

I could get published that wasn't a college newspaper,

zine or blues music newsletter.

30 years ago I started my journalism/writing

career with HARRY, Baltimore’s original underground

counterculture newspaper.

Pre-Internet, HARRY was the only place

I could get published that wasn't a college newspaper,

zine or blues music newsletter.

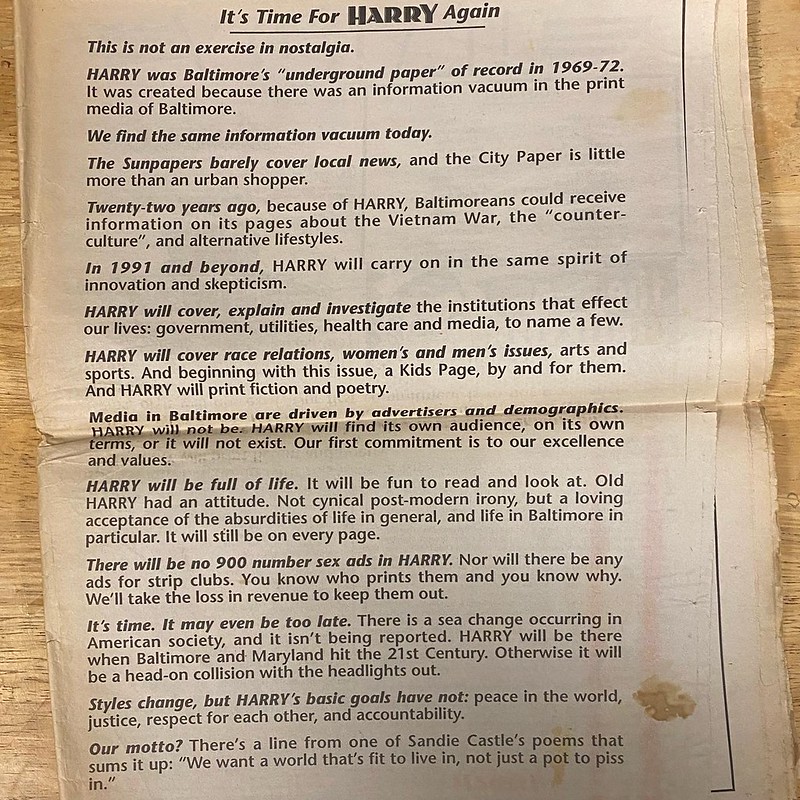

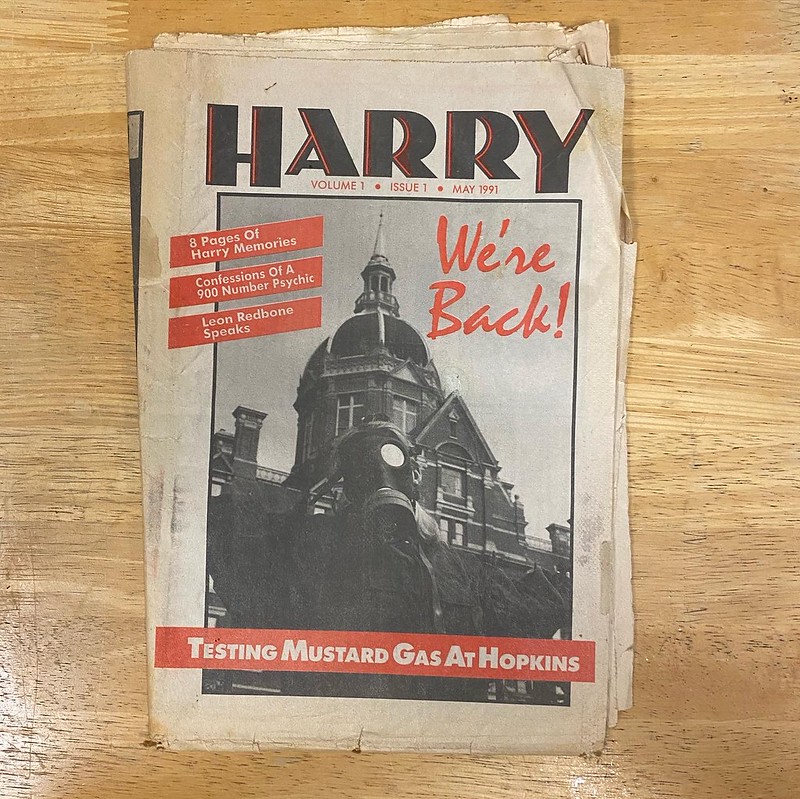

HARRY was around way before I came along in 1991. First rolling off the presses in 1969, HARRY was serious hippie stuff: it was the muckraking newspaper of the streets, of the revolution.

Mind you, at that time, Baltimore was no bastion of counterculture. It was a working class city, with the port and the steel industry providing most of the jobs. That HARRY built a circulation of 8,000 from like-minded freaks in a blue collar town was pretty amazing.

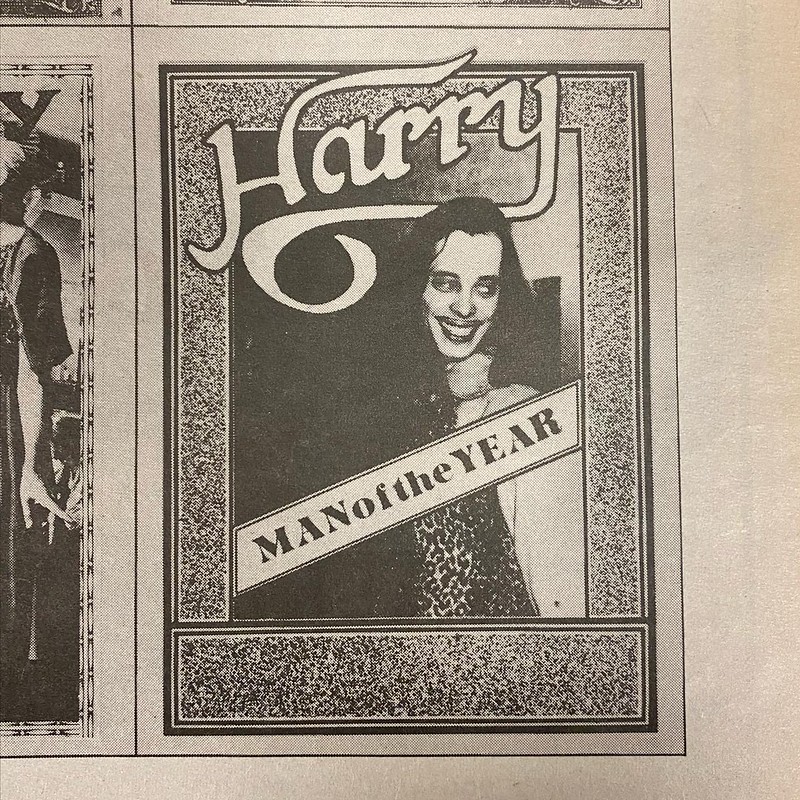

"Editorially, HARRY was opposed to war and capitalism and wanted to replace these with loud music and drugs," recalled P.J. O'Rourke, an editor there who later went on to become a well-known conservative humor writer. The newspaper, published in the "broadside" format, called out police brutality (openly labeling police as "pigs"), and made the case for the legalization of marijuana. They were the first to seriously cover the movies from John Waters and his Dreamland Repertoire, another underground artistic Baltimore troupe.

The staff lived together commune-style in a Baltimore rowhouse, also called Harry. Not surprisingly the office was raided for drugs, and even at one point taken hostage by an extreme far-left group decrying the newspaper's "bourgeois tendencies" (This surprise attack of the office was supposedly the impetus for driving O'Rourke to right-wing politics).

I wonder if Thomas V. D'Antoni, one of the original editors, ever published his story about the undercover law enforcement agency who had lived amongst them. The way he told it to me, anyway, this guy lived at Harry for months, working as the newspaper's staff photographer. He revealed himself on a train trip a few of them took to Florida, for undisclosed reasons. In a layover in Richmond, Va., the guy went to use a pay phone (this was way before the days of cell phones), and when he returned, he told D'Antoni and crew that he himself was in fact an undercover agent, his name wasn't his real name, and he had been reassigned, so it's been good to know you guys. And with that, he walked off, never to be seen again.

Perhaps the police initially considered the Baltimore underground newspaper to be an actual threat to democracy, but when the agency learned what really went on there -- mostly smoking pot, or making a newspaper when the pot ran out -- it was clear that whatever threat that HARRY posed to overthrowing the state would be negligent at best, D'antoni speculated.

But, anyway, you gotta get Thom to tell you that story, which he does much better. Like most all D'Antoni’s stories, it’s hilarious.

Never the most commercial of operations, HARRY struggled along, managing to produce at least 41 issues at random intervals, before it was mercilessly crushed by the forces of capitalism in 1972.

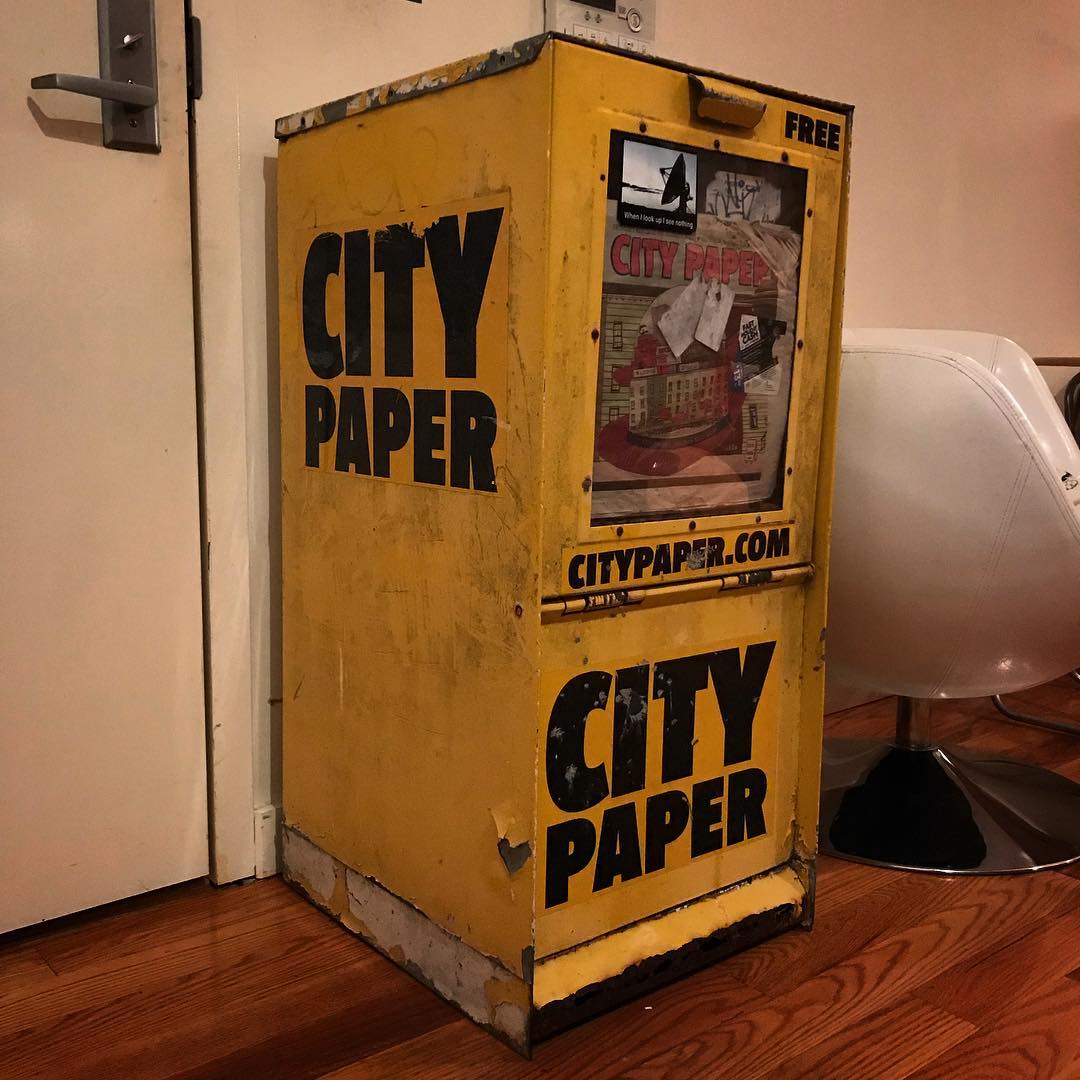

Anyway, in 1991, D'Antoni kicked-started the paper again, partially as a protest against the then-dominant "alternative" paper of the day, City Paper, for the paucity of its local coverage and from the fact that it made obscene money from advertisements for 1-900 sex phone services--a real sore point with some of the paper's more liberal readers, and perhaps to an envious D'Antoni himself.

D'Antoni welcomed this aspiring writer, fresh out of college, with open arms. As it happened, I had just previously worked in the City Paper’s circulation department and so I knew were ALL the City Paper’s newspaper boxes were located. D'Antoni would print these fake "Shitty Paper" fake covers, listing the City Paper's many flaws in his mind, that he could then place in the front display of a few of the City Paper's street boxes (Most notably, the box in front of the City Paper Charles Street office itself). For good measure, copies of the City Paper in that boxes were supplanted with latest issue of HARRY. As memory serves, City Paper management was none too pleased about any of this.

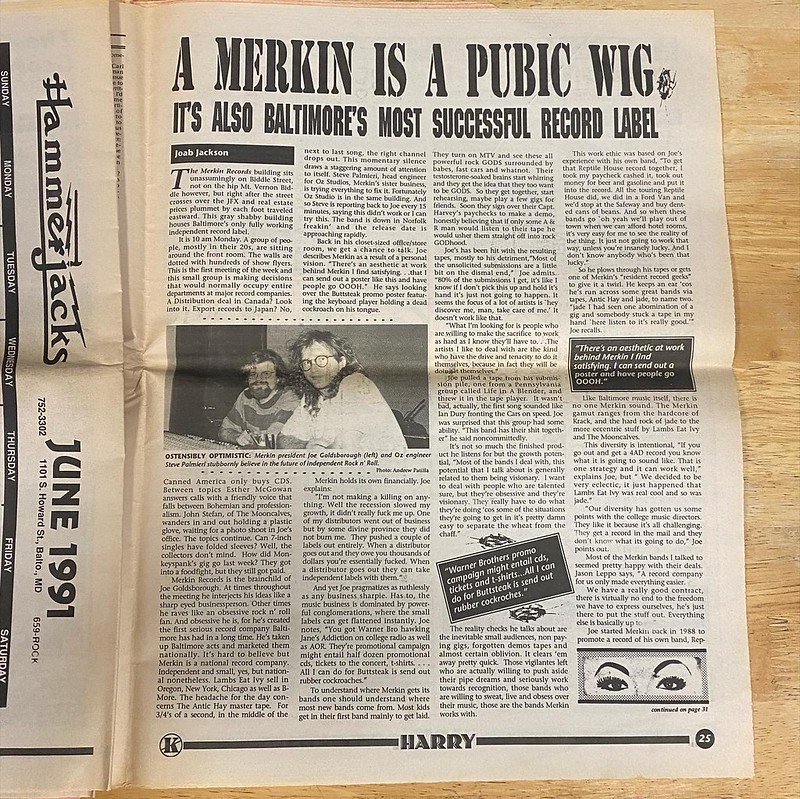

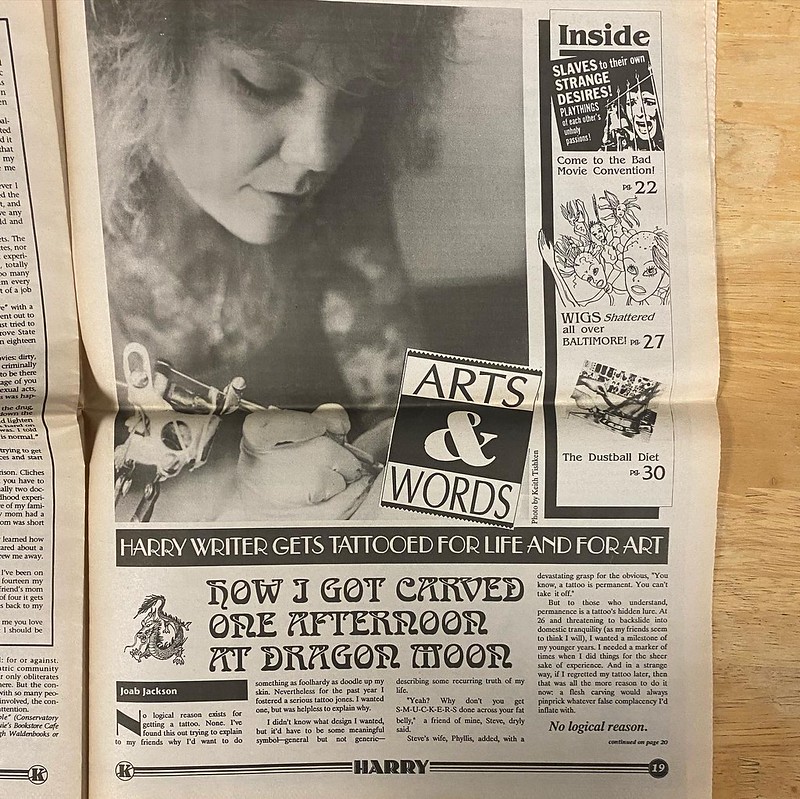

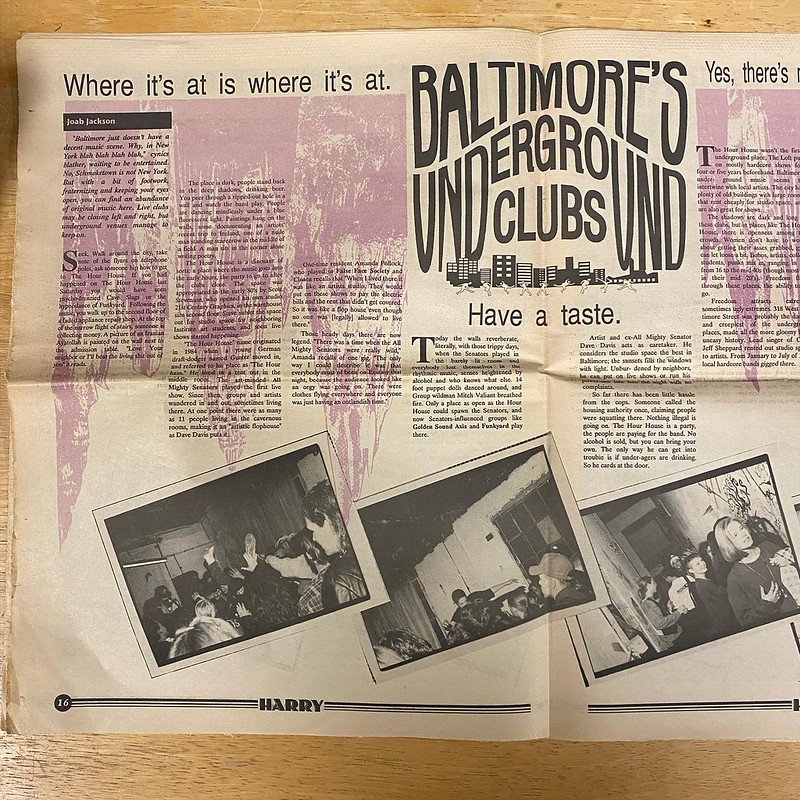

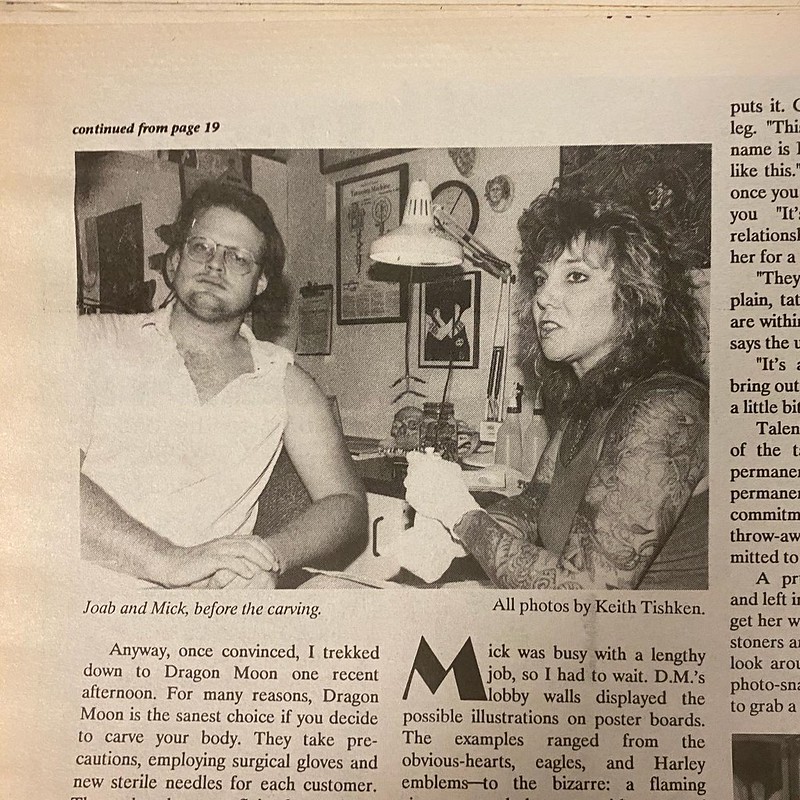

So anyway, I wrote for HARRY a series of dumb stories about getting a tattoo (actually still a bit risqué back then), the live music scene in warehouses, and the plight of psychiatric survivors, the last of which I had to write under a nom de plume because my day job was at the Sheppard Pratt Psychiatric Hospital at the time. That I could write about whatever I wanted was an exhilarating freedom, one that, I would subsequently learn, would not be found in the more corporate gigs down the road.

So, while I wasn't at HARRY during its heyday, but I was damn sure there for the end. It was a heated collective meeting at Thom's house (I believe). A consultant had been brought in to consider the next move for the reconstituted publication, which was financially ailing after six monthly issues.

The consultant's conclusion was to stop printing HARRY. It was over, he told the paper's creators, who just couldn't believe the end was nigh. But there was barely enough money to print the next issue, and after that, what? They had run through the investors' money and while ads were sold to many small local sympathetic businesses (flower shops, art galleries), the sales hardly amounted to anything near the hefty bill from the printer, which required payment upfront. HARRY never could secure the hefty full page ads from car dealerships and phone sex services that buoyed City Paper, or the classified ads that the city's daily newspaper, the Baltimore Sun, relied upon.

The writers, editors and other creatives collectively pleaded to put this one last issue out, something could be figured out for the next one. But there was just no path forward. It was literally the moment that capitalism crushed the cherished ideals of HARRY (again).

I’ve since learned how to do at least some form of journalism for money, but I was lucky to be involved, however tangentially, with this bad-ass newspaper. It connected me with an important past, one that taught me, with no little theatricality, that the written word could be used for something other than furthering the agenda of powerful interests, that it could be a powerful tool for recognizing and building a community of like-minded souls, however marginalized.

I've since carried these ideals into the future, almost-always doomed labor-of-love rogue publications with open ethos and respect for the written word above all else. From HARRY, it was natural progression to throw my hand in with ROX, Art in Progress, New Route, Foster Child, Pigdog Journal, Spock Science Monitor, Bushwick Nation, and even City Paper itself, which folded in 2017.

None of those other local and scene-specific news outlets survived the long haul either, but they were important chroniclers of their times nonetheless. Sometimes, it is less about being the publication-of-record and more about being the publication-of-the-moment. It certainly is a lot more fun, at any rate.