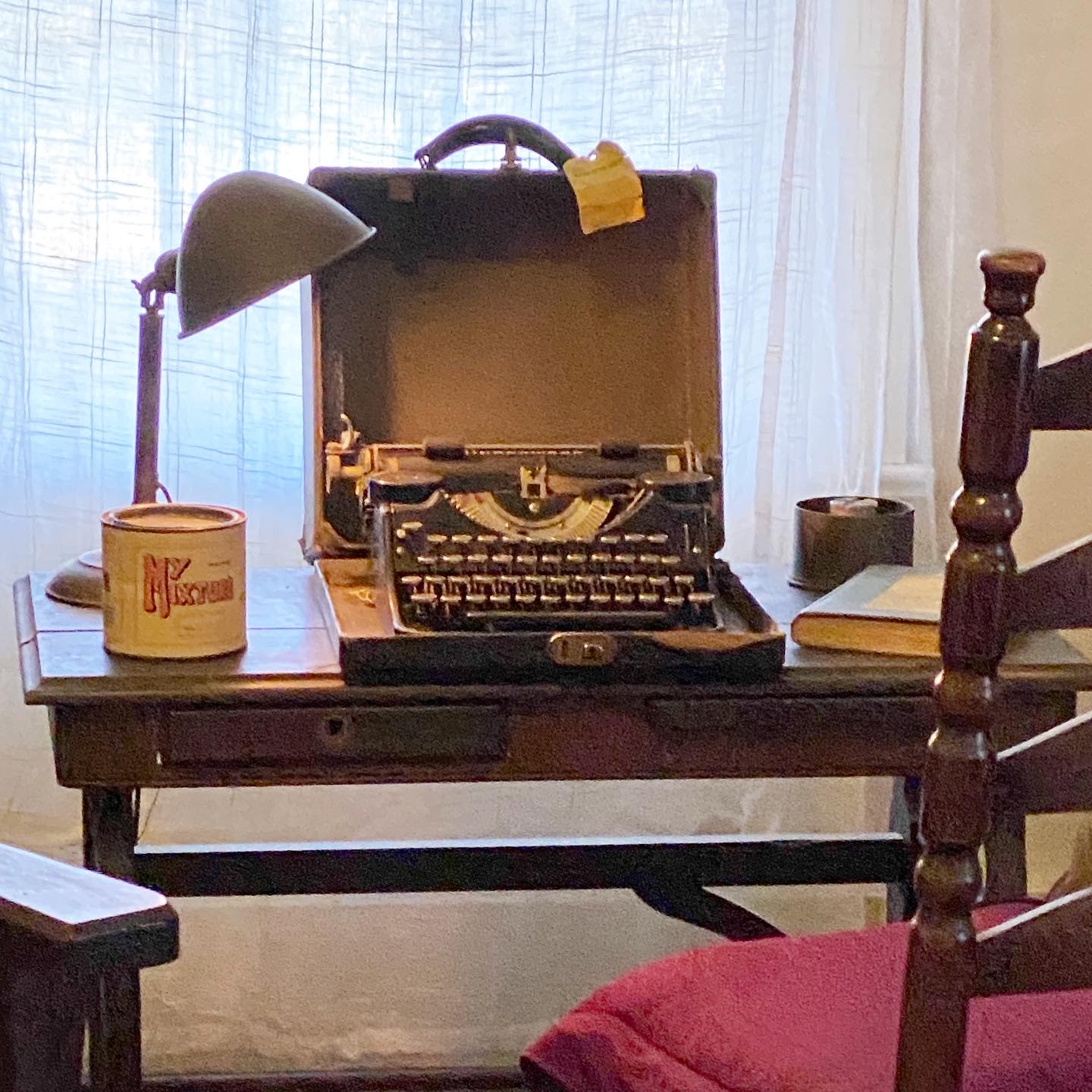

Scenes from William Faulkner's 1932 Southern Gothic classic "Light in August.

"Light in August" follows the life story of Joe Christmas, a man who suffers the indignity, in early 20th century, of being part black, or mulatto, in the south. He is cast off by his father to live in a series of orphanages and ends up working in a lumber yard in a Mississippi small town. He lives in a shack outside a widow's house, and secretly takes up with her. His troubled upbringing catches up with him, and the severity of his situation is exacerbated by the prejudices of the local townfolk.

I

Lena was walking to Mississippi, pregnant, all the way from Alabama, with

35 cents to her name. Her mother died when she was young, then her father,

so she went to live with her brother, senior by 20 years, and his wife,

who was always pregnant, or recovering from pregnancy, it seemed. They lived in a logging town.

Lena stayed in a lean-to out back.

Lena was walking to Mississippi, pregnant, all the way from Alabama, with

35 cents to her name. Her mother died when she was young, then her father,

so she went to live with her brother, senior by 20 years, and his wife,

who was always pregnant, or recovering from pregnancy, it seemed. They lived in a logging town.

Lena stayed in a lean-to out back.

Within a few years, she got pregnant by a local "Sawdust Casanova," who fled town shortly after the news of his pending fatherhood. So she left her home to go find him. He told her his name was 'Lucas Burch,' so she went looking for a man by that name, and was convinced that Lucas would immediately take her in when he saw her next.

She was picked up by a farmer with a cart, who took her back to his homestead, where she could be tended to by his wife, Martha. Martha saw the situation for what it was right away, knowing the naive girl would never see this 'Lucas' fellow again.

"I reckon that even a fool gal don't have to come as far as Mississippi to find out that whatever place she run from ain't going to be a whole lot different or worse than the place she at," the farmer even thought to himself. Nonetheless, Martha opened her piggyback and gave Lena some coins as she continued on her journey.

The next day, the farmer took the traveler to town to catch a wagon into Jefferson. She bought some sardines and ate them as she rode, marveling that it would take her only 30 days to get to Jefferson, Alabama. all the way from Mississippi.

"My, my. A body does get around," she said to herself.

II

A stranger showed up in the sawmill in Jefferson, looking for work. He wore dirtied city clothes and an “arrogant hat,” that irked the workers there. Nonetheless the plant foreman gave the man a job, and he went right to work, in his fancy duds, shoveling the sawdust pile.

He didn't fraternize with the others at all. Joe Christmas, his name was. “What kind of name was “Christmas?” the other workers wondered. He must be a foreigner of some sort.One of the workers, Byron Bunch, thought a lot about the name. “That was the first time Byron remembered that he had ever thought how a man’s name, which is supposed to be just the sound for who he was, can be somehow an augur of what he will do, if other men can only read the meaning in time.”

A few months after Christmas arrived another man appeared at the sawmill for work. Called himself "Brown," like that was the only name he could come up with when it came time to assume a fake identity. This is one of a number of reasons the men around the yard considered him lazy, and dimwitted.

Each week, Brown would lose his paycheck at craps. This puzzled some of the mill workers, but not others: "What makes you think that he could be good at any kind of devilment when he ain't any good at anything as easy as shoveling sawdust?"

Well, soon enough Christmas and Brown became friends, down in the sawdust patch. And one day Christmas quit, and was seen driving around town in a new auto. The two became tight. So the other workers reckoned Brown would quit as well, and sure enough he did.

III

At the edge of Jefferson in a bungalow so hidden away

that the street lamp barely touches it lives a disgraced minister.

Each evening you can see him there, looking out over the street.

Out on the front yard there is a sign that he made himself,

the words spelled out with broken pieces of glass,

offering art lessons, hand-painted Christmas

and anniversary cards and photo development.

At the edge of Jefferson in a bungalow so hidden away

that the street lamp barely touches it lives a disgraced minister.

Each evening you can see him there, looking out over the street.

Out on the front yard there is a sign that he made himself,

the words spelled out with broken pieces of glass,

offering art lessons, hand-painted Christmas

and anniversary cards and photo development.

It also included his name, "Rev. Gail Hightower, D.D." The "D.D." stood for "Done Damned."

Hightower arrived in town some 25 years earlier, with a young wife, as a fresh enthusiastic minister who gushed about requesting to serve the town of Jefferson specifically. Things soon started to chill, however, with the parish soon starting to notice that Hightower's sermons focused a lot of civil war battles, and less about the pressing matters of the community. They were all filled with glory and evil and the calvary and his grandfather, who was killed in combat. On the pulpit, he'd confound this history with absolution and other Biblical matters, which the elders of the church saw as borderline heretical.

Hightower "used religion as though it were a dream. Not a nightmare, but something which went faster than the words in The Book; a sort of cyclone that did not even need to touch the actual earth. And the old men and women did not like that either."

Another issue: Hightower's wife stopped appearing at church each Sunday. When she did, she would wear a "frozen look on her face." And when the town's ladies would visit the minister at their home, the wife was nowhere to be found. Neighbors had claimed that they heard crying in the house at night.

Turned out, she was taking the train into Memphis on some weekends, and one Jefferson woman saw her there enter a hotel with a man.

One Sunday when she was in attendance, she stood up from the back of rear pew where she sat and started screaming and shaking her hands at the pulpit, at her husband. "They did not know whether she was shaking her hands at him or at God." After that day, the church took up a collection to send her to a sanatorium.

When she returned, she resumed her role as the minister's wife, for awhile anyway. "She was now like had the ladies wanted her to be all the time, the way the minister's wife should be." But it soon came to an end: She stopped showing up at church, and her trips to Memphis start to extend in the week.

The minister seemed happy to forget he was ever married. But one Saturday night, on a Memphis trip, she threw herself out of a hotel window. The police had ruled it suicide, even though there was a man in the room with her. The pair had signed in as husband and wife, under false names.

The Jefferson townfolk had found out about it from the Memphis newspaper, and also from the gaggle of reporters who showed up at the church the next morning, where Hightower had decided to press on with his weekly sermon, still with the bombastic overtones of glory and evil.

The parishioners walked out in disgust, and few showed up the following Sunday, when Hightower had elected to continue preaching. By then, he was a mere curiosity, with only reporters from the newspapers and gawkers from the neighboring towns who filled the pews.

So the church had once again taken up a collection for Hightower and asked him to step down. He took the money and quit the church, but did not leave the town, like the townfolk had expected him to. Instead, he bought the bungalow. When a town delegation had come to his door, asking for the money back, he returned the whole sum on the spot, and rumors started circulating that he paid for the house with the insurance money from his wife's death, and that he had might have even had her murdered for the money.

His reputation among the townfolk had continued to haunt him, even though he stayed out of their way as much as possible. He hired a lady of color to cook his meals, but rumors had persisted of him having an affair with her, and so the townfolk spooked her out of working for him. So he hired a man to cook, and an unknown gang beat this guy into quiting. Hightower resigned to do his own cookin.

The town's torment did not end there. Someone had thrown a brick through his window with a note tied to it, demanding that he leave. It was signed by the KKK. He refused.

And he refused to leave when a group of men dragged him out into the woods and tied him to a tree and beat him. He refused to reveal their names to the police, however.

When he delivered a baby of a neighbor who was stillborn, the rumors swirled around town that the baby was his and so he killed it purposefully. By then it was hard to believe that the townfolk actually believed this. "The town had had the habit of saying things about the disgraced minister which they did not believe themselves for too long a time to break themselves of it."

"When anything gets to be a habit, it also manages to get a right good distance away from truth and fact."

Over the years, the town had forgotten Hightower's sins. The whole thing "blew away like an evil wind."

Still, one can wonder why Hightower did not just move out of town. "A fella is more afraid of the trouble he might have than he ever is of the trouble he's already got. He'll cling to trouble he is used to before he'll risk a change," Faulkner wrote.

"A man will talk about how he'd like to escape from living folks. But it's the dead folks that do him the damage. It's the dead ones that lay quiet in one place and don't try to hold him, that he can't escape from."

![]()

Other Quotes

"They say that it is the practiced liar who can deceive. But so often the practiced and chronic liar deceives only himself; it is the man who all his life has been self-convicted of veracity whose lies find quickest credence."

"Maybe it was because like not only finds like, it can't even escape from being found by its like."

Christmas said in that still way of his, 'You don't get enough sleep. Maybe you oughta sleep more."

And Brown said, "How much more?"

And Christmas said, "Maybe from now on."

"I reckon he figured that what Christmas committed was not so much a sin as a mistake."

"The doors were never locked, and it used to be that at whatever hour between dark and dawn that the desire took him, he would enter the house and go to her bedroom and take his sure way through the darkness to her bed. Sometimes she would be awake and waiting and she would speak his name. At others he would waken her with his hard brutal hand and sometimes take her as hard and as brutally before she was good awake.""'Sober now,' Christmas thought. 'Sober and don't know it. Poor bastard.’ He looked at Brown.'Poor bastard. He'll be mad when he wakes up and finds out that he is sober again. Take him maybe a whole hour to get back drunk again.'"

"Nothing can look as lonely as a big man going along an empty street."

"Memory believes before knowing remembers."