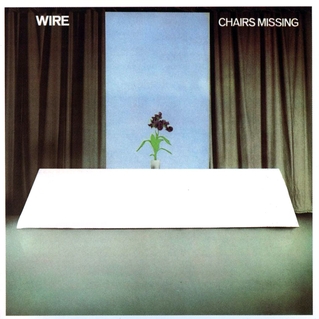

Finally! I've found a punk song about intense ambivalence! From Wire's somewhat maligned second album, "

Chairs Missing,"

regarded as the group's Pink Floyd move, whatever that meant in 1978. Maybe it was the cover, cuz this song is fierce.

Finally! I've found a punk song about intense ambivalence! From Wire's somewhat maligned second album, "

Chairs Missing,"

regarded as the group's Pink Floyd move, whatever that meant in 1978. Maybe it was the cover, cuz this song is fierce.

Cheap DJ: Music of Note

November 05, 2015

October 24, 2015

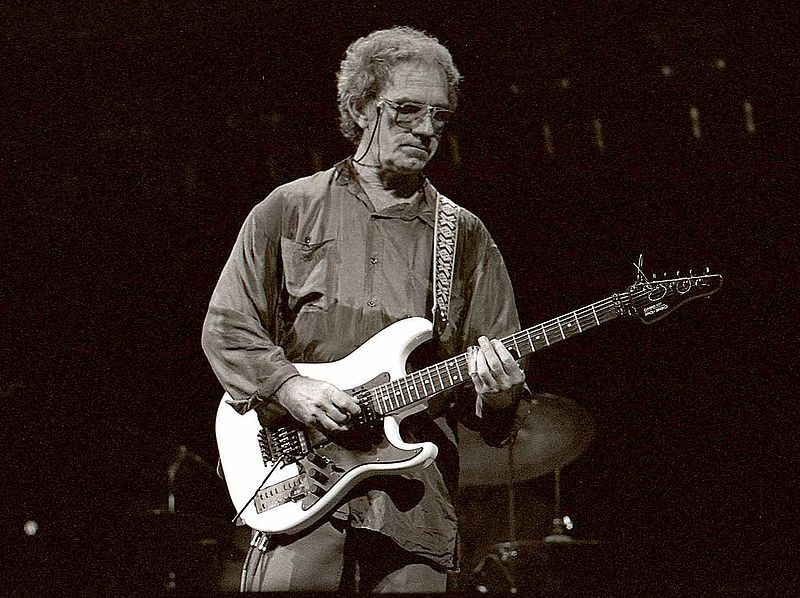

For these three minutes in 1973, Grand Funk Railroad were the smartest kids in the room (cribbing heavily no doubt from

Todd Rundgren, who

produced this track).

For these three minutes in 1973, Grand Funk Railroad were the smartest kids in the room (cribbing heavily no doubt from

Todd Rundgren, who

produced this track).

Something I've noticed while building a playlist for my daily runs is that the classic hard rock bands of the 1970s and 1980s were a lot better at keeping the beat than their more arty "progressive" contemporaries or most of the alternative/indie rock bands that followed.

GFR got its start in Flint Michigan, just up Route 75 from Detroit, a city where, at the time, a band couldn't BUT to learn to rock n' roll. The prog-rockers could wallow in the studios and confabulate imaginary musical worlds, but GFR would slog from town to boring town and boogie HARD every night so everyone across the land could indeed party down, just as the chorus so declaritively lays down. In fact, that is pretty much what this song is entirely about, the hard-charging rust-belt U.S. work ethic.

They were lousy songwriters. Even GFR's best numbers were ham-handed ("Their lyrics creep me out," my girlfriend just said), but for whatever reason, the Flint lunkheads hit this one out of the park. Amurika!

Bet Freddie King still beat them at poker though.

September 11, 2015

The gradual but inevitable dissolution of William Basinski's Disintegration Loop 1.1 -- a brief, ancient tape loop is literally falling to pieces with each repeated play -- is heartbreakingly beautiful.

And the hour-long single-shot accompanying video of the smoke that just continued to billow up so many hours after the WTC collapses captures, for me, the dark undercurrent of what September 11, 2001 felt like.

The song and the event are very closely intertwined.

Basinski's "Disintegration Loops" just preceded 9/11. In fact he finished recording them the morning of. Basinski had a set of his old recordings on tape that he wanted to transfer to digital. The tapes being so old fell apart as they played. So Basinski cut out fragments, made them into small loops, and recorded them as they fell apart playing over and over again. It turned out to be achingly elegiac-- literally the sound of music physically disintegrating, leaving only defiant echoes in the space it occupied.

That evening, the evening of 9/11, Basinski set up a video camera on his roof, in Williamsburg, to record the seemingly undiminishing stream of smoke rising from behind the silhouette of a church across the river. The effect is like an oil painting, though one with rippling smoke and fading light.

May 15, 2015

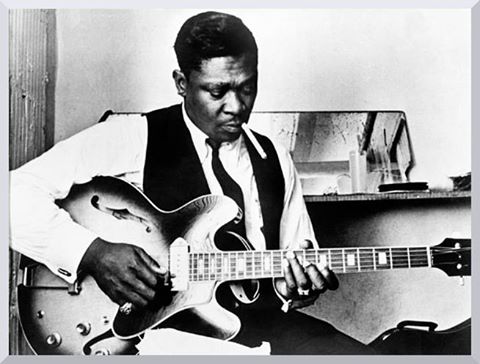

People forget, but B.B. King used to make the young women holler and swoon back in the day, with both his volcanic voice -- as an old City Paper of colleague of mine recently put it -- as well as with emotionally-expressive guitar work. His songs had some pragmatic advice for the menfolk of the time too. ("Don't go upside her head," he advised in one song, "That'll make her a little smarter and she won't let you catch her next time.")

Recorded in Chicago in 1964, just before B.B. crossed over to a mostly white audience of hippies and blues aficionados, "Live at the Regal" may very well be one of the most electrifying live albums ever recorded. Anyone who only vaguely knows of King as some majestic and portly older blues guitarist should give this album a spin. It'll be a revelation, I promise. He drives the audience to the throes of ecstasy...

In Slate, Jack Hamilton called this three-song medley of "Sweet Little Angel," "Itís My Own Fault," and "How Blue Can You Get?" on side one of the album to be "the greatest 12 minutes of live musical performance ever recorded."

R.I.P. B.B. King, the king of the blues. The genre is all but history now.

April 18, 2015

On at least three distinct times, a Bob Dylan song has crashed into my life,

speaking to me directly through the daily din with a lucidity I never thought possible from a pop ditty.

I've never been a 'Dylanologist,' per se. But the man's music has been around for

pretty much my entire life, in one form or another. Some of it is pleasant; A lot of it is crap.

I can't really defend Dylan to anyone otherwise uninclined. He's creaky, cranky and makes a

snarled racket.

I know the lyrics to many Dylan songs practically by heart,

"Maggie's Farm," "Simple Twist of Fate," "One More Cup of Coffee," "Tangled Up in Blue,"

"Like a Rolling Stone," "Desolation Row" -- shit, probably all of

Highway 61 Revisited, come to think of it.

But I learned those songs over time. With these three songs, I remember the exact moment I heard them,

with far more clarity than I remember all the other times around them. Go figure.

I was playing

Bringing It All Back Home quietly on a cheap record player,

not paying much attention because, like I said, I was all up into my own sad shit.

Twenty five years later, I can remember the exact moment Dylan's

voice cut through my internal monologue:

With my attention thus captured, Dylan, with his lonely guitar, laid out a description -- verse by bloody verse --

an angry litany of all the many ways in which this world is fucked:

I can't remember what problem those words solved for me that night. But I felt a

great weight lifted from my shoulders when I heard that "It is not he or she or them or it that you belong to."

You must create your own space in this world, Dylan seemed to be saying to me at the time. In the end, you answer only to yourself.

Live in your dream, or be enslaved in another's. It was a call to personal freedom.

Have you ever been in Old Town Alexandria 6 am on a Saturday morning?

Deserted. Weirdly so. I walked around as the sun rose over all the silent prefabricated colonial town homes.

If "It's Alright Ma" had lessons for the young soul,

"Isis" held nothing but mockery of the very idea of sagely advice.

The narrator in this song is in love with Isis,

who marries him but soon sends him away,

promising that the next time they'll meet, he will be different.

Not knowing what to do, he meets a man at a laundromat who offers to take him on a money-making job of a dubious sort.

He accepts, dreaming of the riches he can bring back Isis. The piano plods on, a fiddle cries alongside Dylan's voice.

Rough was their journey to a set of pyramids encased in ice. But inside was a body that would fetch a good price, the man kept saying.

The man then died. The narrator decides to plod on nonetheless.

When he found the body there with "no jewels, no nothing," it was then realized that his companion, "was just being friendly."

I was captivated by this story as I walked around Alexandria, listening again and again, as attentively as

I would to a dear old friend with a particularly engaging tale. Again, Dylan here is insistent,

like this is a matter he must get across anyone who is listening.

After his journey, the narrator returns to Isis, and the following exchange takes place, which I've come, in the years since, to believe were the

central point to the whole song

Such a casual exchange after such a harrowing journey! Was there a point to this shaggy dog narrative? Fuck I know.

Life just happens, it rolls along like a stream,

wearing down and polishing even the most jagged of rocks. In the end Dylan got back to Isis, through machinations

totally beyond his (and our) understanding. It's O.K. It's all O.K.

Now we're getting into my middle age, and Dylan's as well. His voice is hoarse, tired. Even then, he sounded too old for this.

I was crossing a bridge in Portland, Oregon, the one over the

beautiful Willamette River that cleaves the city. It had been a long day of work, and my mind was crawling to slow. My head was in no place

for extended narratives.

Dylan's croaky gibberish hovered

around the edge of my consciousness for the first six minutes of the song, until the music tensed up slightly and Dylan

unrolled this tale, again calling me, somehow, to pay close attention. If "Isis" is a shaggy dog tale,

this bit is like one of those stories-within-the-story you find in Gothic novels.

This song details an exchange, real or not, that Dylan--lets assume the Dylan is the narrator for our own story telling purposes--has with a waitress in an otherwise unoccupied diner.

This takes place in Boston, on what the narrator assumes (but does not know) is a holiday. Gypsy musicians, amirite?

Dylan sits down at one of the empty tables. A waitress, with "a pretty face and long shiny legs," comes over.

She asks what he'll have.

Dylan leans back looks at her (my embellishment but you can feel all this in the song) and asks, 'What do I look like I want?'

The waitress sizes him up and says "You look like you need hard boiled eggs."

"That's right," Dylan affirms. "Bring me some."

"We're out," the waitress, no fool, responds. "You picked the wrong time to come." (BTW the official Dylan site

obfuscates these lyrics for some reason.

And very badly so too, given how crisp Dylan's retelling of the moment).

This edgy transaction continues. Sensing that her reluctant customer is an artist, she asks him to draw a picture of her. He demurs, politely

at first but firmly insistent:

So, Dylan sketches out a few lines and "then show it for her to see."

I'll pause here just to say how much I love that last line. It's so matter of fact but so slyly melodic as well.

All the seemingly casual lines in this part of the song are crafted with this care, it seems.

Anyway, the waitress, when she sees the results, is aghast, throwing the napkin back down. Now Dylan is insistent,

boldly defending the throwaway drawing, as if it were worth defending in the first place.

"It doesn't look a damn thing like me," she protests. "Oh kind miss, it certainly does," he counters.

He must be joking, she said. "I wish I was," Dylan responds.

The conversation devolves quickly, with the waitresses then accusing Dylan of never reading woman authors.

He haughtily pointed out that he read

Erica Jong.

When she goes away for minute,

Dylan, or his character, slides out of his chair and back to the busy street "where no one is going anywhere," and sliding

just as easily out of my consciousness.

The lyrics so brilliantly capture this ordinary moment of mutually charged-unease between two people. It's totally insignificant,

but the moment becomes personal to me as well. It's a story from a guy I'll probably

never meet, but feel yet know in some mysterious way, somehow.

2015-02-14 If you're over, say, 45, and lived in the states,

"Long Tall Glasses" is pretty much in your DNA, even tho you probably don't remember it now.

And when you hear it again, you'll probably recalled that you hated it.

But, really, back then, whenever it floated over from some nearby radio, you dug it (maybe secretly).

That'd be my guess, anyway.

The young uns, all unencumbered w/ such cultural baggage, are free to enjoy

this kinda bad-ass song from Leo Sayer:

"I was going down the road feeling hungry and cold," is one of the great opening lines ever, and Leo proceeds to spin out a

hobo's tall tale about coming across the ultimate feast ("Yeah, there was ham and there was turkey, there was caviare / and long tall glasses with

wine up to y'are") that he could avail upon only after showing a proficiency in musical footwork.

The lyrics and melody,

sharp and smart throughout, were Broadway musical-worthy, yet the band played it as loose and casually groovy

as any group of scruffy white boys of the era could be.

By those who grew up on AM radio in the 70s, Leo Sayer is primarily remembered (and not always fondly) for

inflicting a

series of

lightweight pop songs,

all of considerable over-ripeness, onto the airwaves. Who bought these singles? It was a mystery to me. But those are

what he is remembered for today.

Surprising now to think that Sayer once carried a bit of street cred, the hippies would have called it. The Who's Roger Daltry and Three Dog Night covered his jams.

He employed some of the Rolling Stone's backing musicians (Bobby Keyes, Nicky Hopkins) in his band, as well as David Bowie's guitarist Earl Slick

and a few of the Booker T & The MG's. He even skirted glam, via

a Bowie-esque singing pantomime stage persona

(which makes no sense but there you go), and by opening for

Roxy Music on

a European tour in 1973-74,

which, alone, is more glam than you'll ever be.

"Long Tall Glasses" was Sayer's first U.S. hit, and it got over on purely on melody, charm, groove and chutzpah.

Many people today still call it "I Can Dance" or "I Can't Dance," and their age-muddled minds confuse it with the much more cartoon-ish

"You're Mama Don't Dance," much to Leo's detriment.

It was rarely a victory for artistic singularity to be assigned

Richard Perry as a producer, though, and Sayer

blanded pretty quickly after "Long Tall Glasses" in the pursuit of the almighty top 40 payout.

He got what he wanted but lost what he had, as they say.

2014-06-26

But, upon reflection, I've come to view the cover as an inspired, even essential, choice. And not just because Clapton, much like some funeral director for talented but under-appreciated genius guitarists, knows how to pay tribute, even if he does carve a bit of the dearly-departed's legacy out for himself (cc: Robert Johnson).

No, the genius of Clapton's cover is that it brings perhaps what is the quinessental

JJ Cale song home from a lifelong journey.

Some songs just travel well through time. They lose none of their gut appeal as they pass from genre to genre. Along the way, they even pick up new friends, as well as a bit of the wisdom and dust of the ages.

This is true, I've noticed, of JJ Cale's "Call Me The Breeze." It's gone from country to techno and back again, serving as both Cale's introduction to the world and, now, the eulogy for his passing.

"Breeze" came into the world as the first song on Cale's debut album,

'Naturally.' In essence, "Breeze" was Cale's calling card.

It was deceptively simple number, clocking in at less than three minutes, with a basic acoustic 12-bar blues guitar shuffle built on a muffled drum machine beat.

Cale's voice is weary, thin and barely present -- defining, and pretty much perfecting, a laid-back style that would carry him well for the following four decades:

Cale scaled everything back here but the slow burn groove of the number itself. And that was plenty. I can't hear this song and not tap along.

The song was all about traveling, lyrically and musically. The loosely rhythmic guitars celebrate the speed of American road: "I might go out to California. Might go down to Georgia, I don't know."

Being on the road to somewhere, or anywhere, the song implied, is essential to remaining alive. "Ain't no change in the weather," Cale dryly sang, "ain't no changes in me."

Ironic that Cale hated touring.

In a 2012 interview with the New York Times, fellow journeyman and Cale fan Neil Young explained the lure of the road:

"For whatever you're doing, for your creative juices, your geography's got a hell of a lot to do with it," Young said. "You really have to be in a good place, and then you have to be either on your way there or on your way from there."

"Breeze," as Cale recorded it, traveled new territory even stylistically. It wasn't quite country. Nor was it folk, or blues, or rock n' roll, at least as people thought about those terms in 1972. But the song suggested all these styles as it briskly rolled along.

Actually, the first -- and still my favorite -- version of this song I knew, came from Lynyrd Skynyrd.

By the early 1980s, when I heard this number, Skynyrd was oft dismissed as a simple-celled southern hard rock boogie band. And they did indeed amp up their version, which was recorded in 1974 (on the awesome '

Second Helping' album, which also contained the first version of the

soon-to-be famous and subsequently even more infamous classic rock anthem "Freebird").

Skynyrd really brought a lot to "Breeze" though, fleshing out many aspects of the song only hinted at

by Cale. If Cale's song was a dusty pickup with two open windows bumping down a long, flat two-lane road,

Skynyrd's version was an air-conditioned Cadillac flying along the interstate: Sleeker perhaps, but faster as well.

This version carries considerable chunks of American musical DNA along for the joyride. Skynyrd's three-guitar attack brought the song to the hard rock crowd. But Ronnie Van Zant's voice is pure country twang, albeit of a Florida swamp variety.

And, day-um, does this number have some forward momentum! For my money, Skynyrd's version is best heard speeding 80 miles an hour down the Interstate.

Ironic too, though more cruelly so, that Ronnie Van Zant, and two other Skynyrds, died on the road. In a sense anyway--they were on their way to

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, for a gig when their plane ran out of fuel and crashed in the deep Mississippi woods.

For the musician, the road can be brutal, even if it does hold great promise.

Legend among the Allman Brothers tribe was that the group named its 1972 album "

Eat a Peach" in honor of recently-deceased leader Duanne Allman, who died crashing his motorcyle -- so the rumor went -- into a peach truck (It was

actually a lumber truck and the inspiration came from an Allamn quote: "Every time Iím in Georgia I eat a peach for peace.Ē).

In any case, "Breeze" went through various other incarnations. Bobby Bare recorded a soul version, John Mayer

cut a comfortably laconic version, and Johnny Cash, along with his his son, had a country take on the number.

Taking the song out to the furthest stretches however, was the U.K. space rock band Spiritualized who in 1992, for their

debut album, drove it to the brink of techno, interpolating it with the Velvet Underground's proto-punk "Run, Run, Run" for good measure:

Earlier this month, Eric Clapton brought "Breeze" back home to its shuffly acoustic roots, recording a version in tribute to Cale, who died last year at the age of 74.

Clapton was heavily influenced by Cale: The British blues guitarist had hits with covers of Oklahoma recluseís "Cocaine" and "After Midnight," and Clapton's sound, especially from "461 Ocean Boulevard" onward borrowed Cale's minimal touch.

Clapton's version of the song serves as the cornerstone for a

soon-to-be-released Cale tribute album. It lumbers a bit more than the orginal, but sounds more rounded out as well:

Oddly enough, even up until Cale died, many of his Tulsa neighbors didn't know he was a musician of international renown; many just thought he was a truck driver.

2014-03-01 It's been a "Maggot Brain" sort of morning... The wicked and despairing guitar solo comes courtesy of Eddie Hazel.

The "Village Voice" had it that Funkadelic leader George Clinton, under the spell of acid, instructed Hazel to play as if

"he had been told his mother was dead, but then learned that it was not true."

Hazel never again scaled such a heights, though he released

a solo album in 1977 that had some pretty tasty '70s porn funk.

2008-01

Who first discovered Skynyrd in the gang of neighborhood hoodlums whom I subsequently took to spending my leisure hours with?

Someone with an older brother probably.

Keep this in mind: Growing up, "Free Bird" was never on our "heavy" rotation--it tested below "Saturday Night Special,"

or "The Needle and the Spoon," as far as Skynyrd went. It kicked later. But at the time, it served as fine accompaniment

for the usual bonding rituals of the pre-mated.

Those were the days. La Grande, as we used to say! But where was I? Sorry, I'm prone to wander off course. "Main point, you're in my way."

Now, saying you like Skynyrd today is showing you're down with your alt-country roots. But admitting you like "Free Bird"

just shows you're some sort of loser, man.

The song is now a punchline of a rock club joke that itself is two decades old (Sullen IndieBand confers

on what song to play next; Lurking hipster yells "Free Bird!" thinking its "ironic").

The song itself sounds bland. It starts with a slide solo and

piano accompaniment that rather crassly evokes the days when Duane Allman could make everything seem ok.

It ends with a three-guitar wank-off longer than any highway you'd care to mention. Crushed in the middle is a simplistic,

somewhat sappy, lament. It's like "Layla" in reverse order, played by monkeys.

Seriously, we admitted "Free Bird" was formulaic even back then. At least three dozen major-label

boogie bands must have been working that very recipe out on the floor-boards, night after night. The various

combo platters of drugs that the kids fed upon left them agreeable to such surge-y noises. Tickles the neurons or some shit.

But why did people kept hollering for "Free Bird" specifically?

I'm gonna tell you why I think that was. Pretty soon.

Now, "Stairway to Heaven"? That's a pretty song. And a rockin' song too. But country gentlemen know it ain't hobbits that inhabit the woods.

"Free Bird" starts off nicely enough. Getting bird calls out of a slide guitar? Pure American folk art,

sappy and clever all at the same time. The song gets noticeably darker though.

Ronnie Van Zant keeps wailing "Lord knows I can't change." "Lord knows I can't change,"

Sounds pretty good after a week of work at some incredibly fucked-up job, with no prospects in sight. "Lord knows I can't change."

Free bird? Yeah, fucking right. The title itself is a cruel joke.

Free to work the rest of your life at some carpet warehouse for $4 an hour. Free to buy a used car that

stops running before you pay it off.

Ronnie's first line is "If I leave here tomorrow..." He KNOWS he can't go anywhere! So its only drunken speculation after that--Ronnie's,

yours, mine and anyone within range of the jukebox in that shitty bar where too many of the off-hours are being spent listening to these types of songs.

There, we can all mouth into our mugs that rock-star gentle "There's-too-many-places-I've-got-to-see" fuck-off-fair-lass line all we want.

It's the only places that line'll get used, however semi-audibly.

By the time the Skynyrds work up to their ending rally--by first erupting into the closest melodic approximation of

violence you'll ever hear in a moderately-civilized drinking establishment, and then breaking into the momentum

of someone hauling-ass from the law--you can, if you're in just the right sort of crappy mood, end up banging

your mug against the table in unision: Each beat more intense than the last, each one with the hope that ride will never end.

And for just over seven glorious minutes, it doesn't.

And there it is. If you follow the song down the path it offers, you'll find the Holy Grail of Rushes, the one that keeps giving.

Not for 40 seconds, or a minute, but for a full seven minutes. For seven minutes that song gives you the freedom from

whatever shithole-of-a-life that you've dug yourself into.

Granted, you must have some pretty heavy grievances to work out if you need to bang glassware on a public tabletop for seven whole minutes.

But man, if you do, Skynyrd will get you through...

Now, what song was it that you wanted to hear?

The first time a Dylan spoke to me directly,

I was a wee lad of 22, lost in my own head,

late at night, sparring with conflicted spirits.

The first time a Dylan spoke to me directly,

I was a wee lad of 22, lost in my own head,

late at night, sparring with conflicted spirits.

Alone you stand with nobody near,

When a trembling distant voice, unclear,

Startles your sleeping ears to hear,

That somebody thinks they really found you

For them that must obey authority,

that they do not respect in any degree,

who despise their jobs, their destinies,

speak jealously of them that are free,

do what they do to be

nothing more than something they invest in.

2:

"Isis" (1975)

Flash forward maybe 15 years. All those existential concerns of my early-20s

had simply dissipated by then. "Isis" I heard

just as after I dropped my girlfriend off at D.C. National Airport for a very early flight.

I'd agreed to have an early brunch with a friend who lived nearby, so I had a few hours to kill in a

pre-dawn hours in Old Town Alexandria.

Flash forward maybe 15 years. All those existential concerns of my early-20s

had simply dissipated by then. "Isis" I heard

just as after I dropped my girlfriend off at D.C. National Airport for a very early flight.

I'd agreed to have an early brunch with a friend who lived nearby, so I had a few hours to kill in a

pre-dawn hours in Old Town Alexandria.

She said, "Where ya been?" I said, "No place special"

She said, "You look different." I said, "Well, I guess."

She said, "You been gone." I said, "That's only natural,"

She said, "You gonna stay?" I said, "If you want me to, yes."

3:

"Highlands" (1997)

Fast forward another 10 years or so. I happed across this ambling 16-minute jaunt again by way of the random shuffle, while I was walking around.

Fast forward another 10 years or so. I happed across this ambling 16-minute jaunt again by way of the random shuffle, while I was walking around.

I say, "I would if I could but ... I don't do sketches from memory."

"Well," she says, "I'm right here in front of you. Or haven't you looked?"

I say, "All right, I know, but I ... don't have my drawing book."

She gives me a napkin. She says, "You can do it [slurred as 'doodle'] on that."

I say, "Yes I could, but ... I don't know where my pencil is at."

She pulls one out, from behind her ear.

She says, "All right now, go ahead, draw me, I'm standing right here"

![]()

![]()

When I heard Eric Clapton had

covered JJ Cale's "Call Me the Breeze" as a tribute to Cale's passing, my initial reaction was despair. Must this man continue beat the life from all Cale's songs? A Clapton fan I am not, you can tell.

When I heard Eric Clapton had

covered JJ Cale's "Call Me the Breeze" as a tribute to Cale's passing, my initial reaction was despair. Must this man continue beat the life from all Cale's songs? A Clapton fan I am not, you can tell.

The song also has some fine barrel house piano, and the horns evoke not only the Muscle Shoals soul of the day, but the swing jazz from decades earlier as well.

The song also has some fine barrel house piano, and the horns evoke not only the Muscle Shoals soul of the day, but the swing jazz from decades earlier as well.

![]()

![]()

This is what I learned from the Lynyrd Skynyrd song "

Free Bird": The long road from cool to silly is paved with time.

This is what I learned from the Lynyrd Skynyrd song "

Free Bird": The long road from cool to silly is paved with time.

See Also: