Photography is not allowed inside the Museum of Jurassic Technology, but in a sense it doesn’t matter. Photos of the exhibits would be meaningless, if not harmful to the outside world.

Photography is not allowed inside the Museum of Jurassic Technology, but in a sense it doesn’t matter. Photos of the exhibits would be meaningless, if not harmful to the outside world.

The proprietor, David Hildebrand Wilson, offers little insight regarding the place, which occupies an unassuming Venice Boulevard rowhome in Culver City California – deep in the heart of Los Angeles.

Wilson has said the institute is a small natural history museum of sorts, with an emphasis on "curiosities and technical innovation." But even the most thorough of notetaking -- The giftshop helpfully sells notebooks and heavyweight pens – will still leave you wondering what you are seeing, and what you thought you learned. The Museum of Jurassic Technology is not a museum of natural artifacts as much as it is a museum of how we construct truth around these artifacts.

The word ‘museum' is built on the word 'muse,' and thus a museum should the provide the attendee with the space to quietly contemplate the wonders of the world, an introductory video helpfully explains as you enter the place.

The video also explains that the idea of devoting a museum to natural wonders of the world – as opposed to the art of man –arose from in the 16th century, as humanism flourished in the wake of the Renaissance.

Until then, wealthy people gathered scientific curiosities and oddities into collections (“wonder cabinets”), for possible future scientific interest and appreciation; During the Dark Ages, churches took possessions of many of these collections. After the 16th centuries many of these cabinets of curiosities coalesced into local and regional museums, which brought uniformity in how such artifacts were evaluated and presented.

In effect, the Museum of Jurassic Technology questions the very idea of a “museum” itself. What is it presenting? Why is it presenting this thing and not another? How does the way an artifact is shown shape our thinking about it? And who are these museum curators anyway?

Jurassic Tech consists of dozens of small exhibits cozily intermingled in the cramped home. As you walk through the museum, you hear the various sounds leaking in from the tiny halls—some music, loud clicks and whirrs, short videos, rando sound effects.

Each exhibit is a puzzle of sorts, built with the outdated trappings of a small-town natural history museum – dusty cases of artifacts in boutique lighting, blurry black n white photographs, pushbutton headphone sets to listen in on benign scientific narratives. Pedestals are haphazardly placed around the rooms, at different heights. And many rooms are shrouded in near darkness.

One of the first, and seemingly one of the oldest, displays you see when you enter is “Protective Auditory Mimicry,” which offers no explanatory information whatsoever. The display case holds two objects, a preserved beetle and a gemstone. Each is held aloft by a small rod pinned to a backdrop, and is accompanied by a light: a red light for a beetle, a green light for the gem. A relay hidden in the back of the display case audibly clicks between illuminating the two lights back and forth. When you put on the headphones that accompany the display case, you hear a wavery erratically rhythmic buzzing sound that changes pitches in synchroneity to the lights, with the beetle having the lower pitch of the two.

Could it be an illustration of the acoustic properties of these objects as compared to one another? What could the importance of such a thing possibly be? No Clue.

Right next to this last contraption is what the museum claims to be an almond (11mm by 13mm) with a number of very tiny scenes carved right into it. Allegedly, a man can be seen playing a flute with a number of barnyard animals behind him. The display helpfully provides mirrors all around the almond as well as a magnifying glass focused on the nut. If you squint you might be able to make something like that out. Or not. It’s hard to tell, really.

After a while, you may start to notice the subjects of these exhibits – which can be about anything like “vulgar remedies” (folk medicine) dogs or self-made mobile homes of California in the early 20th century – are of dubious nature. Most of these tiny exhibits go through considerable lengths (the magnifying glass, the mirrors) to bring authenticity to themselves.

But most of these informational aids seem to only serve to confuse the viewer even more: Complex contraptions are displayed with no context. Video accompanies other exhibits, but their explanations are woefully incomplete, irrelevant or showing only a staggering amount of text. Captions sometime partially overlap the photos themselves.

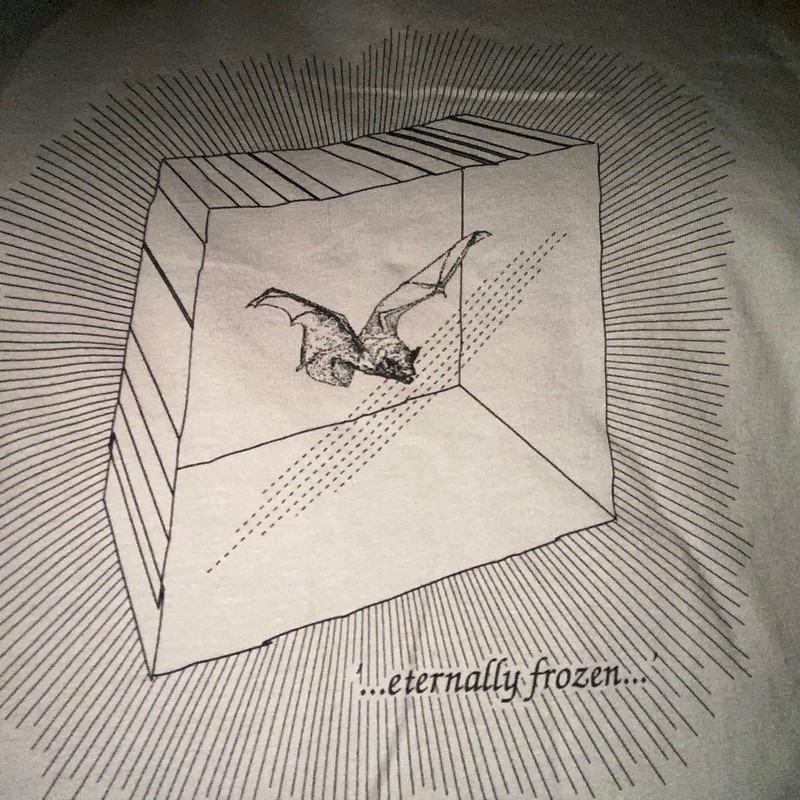

The exhibit “Deprong Mori of the Tripiscum Plateau” best illustrates this tendency. It so expertly tells the story of a South American “Deprong Mori” bat that could fly through solid objects with such a convincing story line and all the associated detail that the viewer may not even question the utter impossibility of such a thing.

Each artifact in this large display case is lit up at the appropriate time as the narrator goes through the story of how the elusive bat was allegedly captured. A 19th century anthropologist, Bernard Maston, first heard about the “Piercing Devil,” as the locals described this “small demon” that they said could penetrate solid objects, such as a dwelling or even a person.

Maston’s field notes were all but forgotten for another century until another researcher, Donald Griffith, ran across them. He travelled to South America to find the super-elusive bat.

Griffith reasoned that because bats use echolocation, a sort of natural built-in radar, to probe their surroundings and fly around obstacles, this particular species of bat must have used electromagnetic (rather than sonic) emissions that it was indeed able to detect matter in such fine nuance that it could “fly unharmed through solid objects.”

The researcher and his companions had much difficulty capturing this bat, though, which easily swerved around any sort of netting they could devise. Finally, Griffith resorted to a trap that consisted of pentagonal arrangement of huge solid lead walls, 8 inches thick, 200 feet in length 20 feet high, which entrapped the creature within one wall.

It is perhaps only then that the museum visitor may pause and wonder,“Lead walls, 200 feet long and 20 tall? How would that be possible in the jungle?” Or maybe they’d realize that while an electronic signal may pass through an object, but another object would not be able to, a point artfully eluded by the narrative. In any case, it may take a minute or two to realize that none of the information delivered in this most staid 1950s-era, multimedia educational format, was a bit true.

Such outright fabrications are not errors in presentation. The true content of the museum are the presentations, not the content itself. Jurassic Tech reveals the mechanisms of how museums present artifacts as worthy of our attention. And beyond the museum, it brings in the question of how we constitute truth itself, and how malleable that truth can be for the individual.

![]()

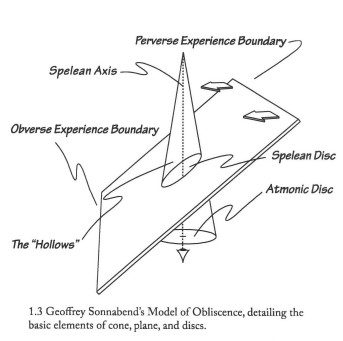

In the center of this rowhouse-sized museum is a theater dedicated to a “forgotten” theory of memory by (arguably fictional) Geoffrey Sonnabend, summarized as “Obliscence: The Theory of Forgetting and the Problem of Matter.” https://www.gwern.net/docs/philosophy/mind/1991-worth-geoffreysonnabendobliscencetheoriesofforgettingandtheproblemofmatter.pdf.) The “theater” consists of a 3-person bench in front of a small video display surrounded by conical models of Sonnabend’s ideas.

We live in an eternally fleeting present, our memory is an illusion, and what we think we remember is mostly a fabrication, the female narrator in the video tells us, presumably translating from that French speaker heard in the background, along with snippets of an opera singer.

The opera singer, Nadalena Delani, died in an auto crash the day after Sonnabend saw her perform. He dedicated his research to Delani, who had suffered from a lack of short-term memory. There is an adjoining exhibit about Delani’s career, in the next hall over.

In the display cases are a set of model cones and planes intersecting each other at various angles. The cone, we are led to understand, represents our view of the world at any given moment. Sonnabend called it the “cone of confabulation.”

If you put a line down the center of the cone, it could represent our attention. The further from the line in the cone, the more distant it is from our immediate notice. The plane represents an experience as it moves through our cone of attention. The greater the tilt of the plane, the less likely we are to notice anything about it, so explains the video. Once the plane no longer intersects with the cone, it ceases to be an experience, and the memory quickly fades. (If the plane travels in the opposite direction, by the way, it is Deja vu, or the experiencing of something that has happened yet.)

Sounds like a reasonable enough theory about how memory works, if we think about it at all. Was there an actual Sonnabend? Do a Google search, however, and the only other mentions of Sonnabend (and Delani) lead only back to the museum itself.

And beyond its inherent disruption Jurassic Tech poses to museum industry, or to our understanding of the truth itself, there lies a certain poetry to the ideas the institute chooses to highlight, themselves, a forever intelligible thematic string tying together Russian Soviet space dogs to the 19th century science of manmade gems. At the top floor of this wonderful gallery of oddities is an open air tea room, situated within a lush rooftop garden. There you are invited to enjoy a cup of tea and a cookie, and contemplate what you have just experienced.